Stoic Camp New York 2015, the first and hopefully not the last of its kind (fate permitting) was a resounding success. My friend Greg Lopez, who runs the New York City Stoics meetup, and I guided twelve people interested in learning Stoicism for three full days in the beautiful setting of Stony Point, NY, on the Hudson River.

Stoic Camp New York 2015, the first and hopefully not the last of its kind (fate permitting) was a resounding success. My friend Greg Lopez, who runs the New York City Stoics meetup, and I guided twelve people interested in learning Stoicism for three full days in the beautiful setting of Stony Point, NY, on the Hudson River.

We had a full schedule, beginning on the first evening with a discussion of why one might want to adopt, or develop, a philosophy of life (not necessarily Stoicism), followed by an overview of Stoic philosophy. From the beginning, we encouraged our students to keep notes, and in particular to build their own “handbook” (inspired by Epictetus’ Enchiridion, of course), where they would write down Stoic quotes they found particularly inspiring. We also advised them to keep a daily journal (modeled after Marcus’ Meditations), writing down their thoughts about the challenges of the day and how they handled them.

The first full day of Camp started with a morning session introducing Stoicism in a bit more detail, using ancient sources. We began with a discussion of Plato’s Euthydemus, where Socrates debates two Sophists and argues that wisdom is the Chief Good — an idea the Stoics took as foundational to their own philosophy. We then moved to book III of Cicero’s De Finibus Bonorum et Malorum, which presents the Stoic system in a dialogue between Cicero himself and Cato the Younger. Finally, we examined the presentation of Stoicism found in Diogenes Laertius’ Lives and Opinions of the Eminent Philosophers.

In the afternoon of the first full day we got down to the task of tackling Stoicism head on. We started with readings and a discussion on the Discipline of Desire and its connection with Stoic “physics,” alternating passages from Epictetus’ Enchiridion and Marcus’ Meditations.

The same pattern was repeated on the morning of the second full day, this time exploring the Discipline of Action and its relation to Stoic ethics. We also debated practical aspects of Action, in particular when it comes to how to deal with other people — a subject about which both Epictetus and Marcus have a lot to say!

The afternoon and evening where devoted to the Discipline of Assent and its relation to Stoic logic, followed by another practical session on Stoic mindfulness. Here Greg, who is actually a practicing Buddhist with a keen interest in Stoicism, was very helpful in explaining the differences between Stoic and Buddhist “mindfulness.” Although Buddhists have evolved a variety of approaches to mindfulness, and a number of meditation practices, the most basic difference, according to Greg, is that the Stoic approach is “analytic,” meaning that it focuses on verbal-logical analysis of problems, while the Buddhist one is anti-analytic, meaning that it focuses instead on the phenomenology of conscious experience.

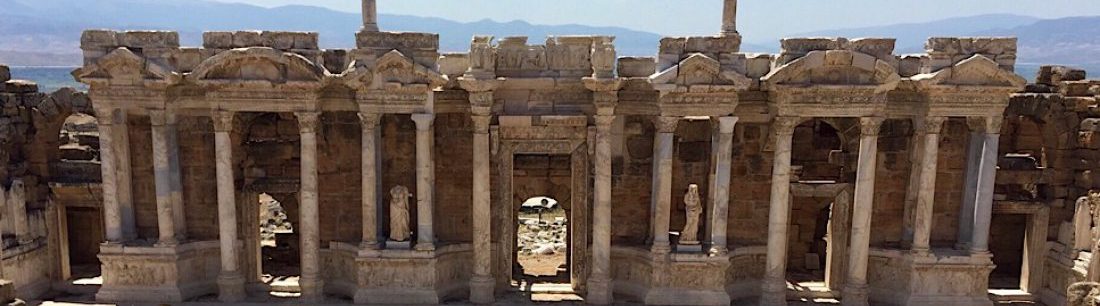

The last (half) day began with a guided meditation at sunrise (see photo), in the spirit of the ancient Pythagoreans, according to Marcus:

“The Pythagoreans bid us in the morning look to the heavens that we may be reminded of those bodies that continually do the same things and in the same manner perform their work, and also be reminded of their purity and nudity. For there is no veil over a star.” (Meditations, XI.27)

We then reconvened after breakfast for a summary and discussion of a number of Stoic techniques that participants could take home for further practice. I list them here, together with the proper references, again either from the Enchiridion or from the Meditations:

- Reminders (Enchiridion 3, 11)

- Otherize (Enchiridion 26)

- Renunciation (Meditations V.15)

- View from above (Meditations VII.48, IX.32, XII.24 third exercise)

- Reserve Clause (Meditations IV.1, V.20, VI.50, VIII.41, XI.37)

- Why am I doing this? (Meditations IV.2, VIII.2)

- Speak little and well (Enchiridion 33.2)

- Chose your company well (Enchiridion 33.6)

- Respond to insults win humor (Enchiridion 33.9)

- Don’t speak too much about yourself (Enchiridion 33.14)

- Speak without judging (Enchiridion 45)

- Morning meditation on others (Meditations II.1, X.13)

- Take another’s perspective (Meditations VII.26, IX.34)

- How did s/he not sin? (Meditations IX.38)

- When offended… (Meditations II.18)

- Examine impressions (Enchiridion 1.5)

- How can I use virtue here? (Enchiridion 10)

- Decomposition exercise (Meditations 6.13, 11.2, 11.16)

- Rebutting thoughts (Meditations 11.19)

- Pause (Enchiridion 20)

- Decomposing an impression (Meditations III.11, VIII.11, XII.10)

- Acknowledging others’ virtues (Meditations I, VI.48)

- Keep athand principles (Meditations III.13, IV.3, V.16, VII.2)

- Keep change and death in mind (Meditations X.11, X.18, X.19, X.29, XII

How did people react to Stoic Camp? The initial, informal feedback was highly positive, but we actually followed up with a detailed anonymous survey to allow participants to express their opinions on a number of aspects of the experience. Here are the highlights (at the time of writing, 10 responses out of 12 participants):

How enjoyable did you find Stoic Camp NY 2015? 100% answered Very enjoyable.

How useful did you find Stoic Camp NY 2015? 100% answered Extremely useful.

What did you think about the amount of reading assigned? Here 70% answered Just right, 20% Too much – give less next time (slackers!), and 10% Too little – I would have like to have read more.

What did you think about the sources that were chosen? 50% said Great and 50% Good.

Did you find the exercise of copying passages that resonated with you into your notebook to be useful? 70% Yes, I found it useful, 20% No, because I didn’t understand we should re-copy passages into a notebook. I did highlight key passages, though, and 10% No – I tried it but it didn’t seem useful or didn’t have enough time.

Did you find debating with yourself in a Stoic manner in your notebook to be useful? 60% said I did it at Camp and found it useful, 30% I didn’t find much need to do it at Camp since I didn’t have many troubling thoughts to debate, but I plan to do it now because it sounds useful, and 10% I didn’t and probably won’t do it because I still don’t understand the material well enough to debate myself Stoically.

Did you find the “homework” mini-essays summarizing the three disciplines and fields in your own words to be useful? 90% said I did them and found them useful, 10% said I didn’t do them, but I wish I did.

Did you find the in-session mini-essays to be useful on the whole? 100% answered I did them and found them to be useful.

Did you find the morning sunrise session on Sunday to be a good experience for you? 70% Yes, 10% No, 10% I didn’t attend, but wish I did, and 10% I didn’t attend, and am fine with the fact that I didn’t.

And finally: Would you attend Stoic Camp NY 2016 if it occurs? 60% said Yes, but only if we covered new material and concepts, 40% said Yes, even if it mostly repeats the material – I’m sure I could learn more from the same materials and enjoy a repeat experience!

Will there be a Stoic Camp NY 2016? Hopefully, fate permitting, and assuming that Greg and I can find the time to organize it. Meanwhile, a full handbook for the Camp, with all pertinent readings and some notes, is available for download here.

Thanks for this writeup and the linked resources. The exercises of debating yourself in a notebook/journal and mini-essay writing sounded very useful. Please elaborate on these and how to do them. Congrats to the organizers and participants!

LikeLike

Thanks for making the handbook available. You have produced what seems to be a very good summary of Stoic practice. That 100% indicated they would attend the next camp is very positive.

And now my question. In my life I have found that great things are achieved when I passionately commit to a truly challenging goal, when I strain every sinew of my being to subduing, circumventing or destroying obstacles(even ruthlessly), when my life is consumed by my commitment to this one goal to the exclusion of all else and regardless of cost.

And yet when I read about Stoicism it seems to be the antithesis of this attitude with its emphasis on stability, balance, even-handedness and equanimity. Have I mis-read Stoicism? Can the two attitudes be reconciled within Stoicism?

LikeLike

labnut,

“Have I mis-read Stoicism? Can the two attitudes be reconciled within Stoicism?”

Yes and no. On the one hand, it is not the case — contra popular understanding — that Stoicism is about suppressing emotions. It is rather about not “giving assent” to negative and disruptive emotions (anger, fear) while at the same time cultivating positive emotions (joy, a sense of justice).

On the other hand, it must be said that seems to be a degree of detachment inherent in the practice of Stoicism (just like there is, I believe, in the practice of Buddhism). And that may or may not be one’s cup of tea.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m a Rortian pragmatist (to some ballpark approximation) who is trying to be more of an activist. But it seems that at least some of the Stoics’ code fits me.

LikeLike

Thanks Massimo.

This article(http://stanford.io/1rX2LRE) by Carlin Barton sort of summarises her book Roman Honor. In the article she says:

“The Crucible of the Contest – As gold is proven by fire, so are we by ordeals.(Minucius Felix, Octavius 36.9)

Virtus and the honores won in the contest were shining and volatile; competition produced a heightened sense of vividness, a brilliant, gleaming, resplendent existence. The man of honor was speciosus, illustris, clarus, nobilis, splendidus; the woman of honor was, in addition, casta, pura, candida. At the same time, to produce this exalted state, the good competition obeyed restrictions; it needed to be: a) circumscribed in time and space; b) governed by rules known and accepted by the rival parties; c) strenuous (requiring an equal or greater-than-equal opponent); d) witnessed.

To have a glowing spirit one needed to expend one’s energy in a continuous series of ordeals. Labor, industria and disciplina were, for the Romans, the strenuous exertions that one made in undergoing the trial and in shouldering the heavy burden. In labores and pericula one demonstrated effective energy, virtus. There was no virtus, in the republic, without the demonstration of will. The absence of energy (inertia, desidia, ignavia, socordia) was non-being. In inactivity the spirit froze.”

She talks about:

“the Roman discrimen, the “Moment of Truth,” the equivocal and ardent moment when, before the eyes of others, you gambled what you were. This was the agon, the contest when truth was not so much revealed as created, realized, willed in the most intense and visceral way, the truth of one’s being, the truth of being.”

This is what I meant, the discremen, “ the “Moment of Truth,” the equivocal and ardent moment when, before the eyes of others, you gambled what you were“.

My limited exposure to Stoicism suggests that this idea is foreign to Stoicism and yet the Romans were, at least in part, Stoics.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks very much for your report on the Stoic camp, Massimo. Greg Lopez is a friend of mine, so it was interesting to hear of his interpretation of Buddhist mindfulness meditation as “anti-analytic”. I think it’s right to say that Buddhist meditation eschews what might be termed “verbal-logical analysis”, and to that extent is anti-analytic, nevertheless mindfulness meditation is intimately related with the Seven Factors of Awakening (satta sambojjhaṅgā), the second of which (dhamma vicaya) is variously translated “analysis of qualities”, “discrimination of states”, “investigation of dhammas“, etc.

In much of the later tradition this aspect of mindfulness meditation is downplayed, but it is an essential part of being mindful. Mindfulness involves the discrimination and analysis of all aspects of “the phenomenology of conscious experience”. Inter alia this involves knowing when one is standing or sitting, having a pleasant or painful experience, when one is angry or not angry, greedy or not greedy, aversive or not aversive, sleepy or awake, worried or not, doubtful or not, and so on. One is then to witness for oneself how these states causally interrelate, how for instance greed or anger in oneself lead to pain in oneself, or how release of clinging and self-identification leads to peace. To that extent, Buddhist mindfulness is analytic of phenomenal experience.

Nevertheless it is correct to note that Buddhist meditation is not “meditation” in let us say the Cartesian sense of “sitting around thinking logically about things”. If Stoic meditation is more Cartesian then they will indeed be different practices.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Massimo, just a note to tell you how much I’m enjoying Footnotes to Plato. In this post, what particularly caught my attention was Greg’s take on differentiating Stoic and Buddhist uses of “mindfulness.” Perhaps, you might encourage Greg to elaborate on this distinction in a future post.

A personal anecdote from the late 1970’s when I was reading some selected writings of R. H. Blyth on Zen Buddhism compiled by Frederick Franck. Blyth is always challenging despite sometimes seeming to strain at taking the iconoclastic route. Late one night, I was reading his commentary on The Hsinhsinming when I needed to urinate. Instead of placing the book down, I decided to multi-task and of course in my fumbling about, I dropped the book into the toilet. I fished it out and laughing aloud sat on the bathroom floor patiently drying it. I came to refer to this episode as my “micro-satori.”

Anyway, if anyone is interested, there is a transcription of Blyth’s commentary here:

http://terebess.hu/english/hsin2.html

LikeLiked by 2 people

James:

As for and example of how to debate yourself in a journal when troubles arise, the whole of Marcus Aurelius’ Meditations is exactly that exercise, and so serves as a great example of how to do this. As for other mini-essays, they were topic-specific at camp. They included things like describing how someone who you were offended by in the past may not have actually been acting “wrongly” (based on Meditations 9.38) and thinking about others’ virtues (based on Meditations book 1 and 6.48).

Doug:

I completely agree with you, and would also add that some First Foundation practices such as the 32 parts and four elements could also be said to be “analytic” in how you’re using the term. I (hopefully) made clear at Stoic Camp that I was using “analytic” in the verbal-logical sense you spoke of.

I would also add that there are some Stoic practices that we brought up at camp that are somewhat analytic in the sense you’re using the term as well. Specifically, there are several passages in Marcus’ Meditations where he uses “decomposition” exercises in order to quell desire (see 3.11, 6.13, 8.11, 11,2, 11.16, and 12.10 for example). These sometimes seem to have a discursive component, and other times not necessarily.

One final addition that I also hope to have made clear at Camp was that when talking about the differences in Stoic and Buddhist “analysis,” I was focusing mainly on early Buddhist practices since that’s what I’m most familiar with. It’s my limited understanding that some later traditions, such as Gelug, do actually train their monks quite a bit in logical analysis and dialectic. As usual, it’s hard to paint “Buddhism” with a broad brush.

LikeLiked by 2 people

The contrast between Stoic meditation and Buddhist meditation has troubled me for some time. Buddhist meditation has a large following so it offers something and yet I could gain nothing from it. Buddhists would say I did not understand it or practised it wrongly but still I made no progress.

It was only when I discovered the Catholic practice of Lectio Divina(for Bible reading) that I began to see that Stoic meditation and Buddhist meditation were the two sides of the same coin, that each was necessary to the other. To make this clearer I will explain Lectio Divina in secular terms.

Lectio Divina has four stages

1. Lectio or reading. This is the preparatory step. The stage is defined and other issues are set aside. It can be the reading of some relevant text. It can be also be a calling to mind of recent events, some situation or a troubling issue. Once the stage is set one can pass on to meditatio.

2. Meditatio or reflection. This is where we reflect upon the text, problem or situation, turning it over in our mind and examining its contours. it is a relaxed consideration of the issue and probably corresponds to Stoic meditation.

3. Oratio or response. Here we set our thinking aside, relaxing our cognitive constraints. This opens up space for intuition or inner voice. It is a preparation for the inner response we will encounter in contemplatio. This corresponds with Buddhist meditation.

4. Contemplatio or restful contemplation. In restful contemplation we listen to our intuitions or inner voice. We listen with the deepest part of our inner being and are gradually transformed from within, which then becomes a moment of realisation, of clarity, an ‘aha’ moment.

In this way Lectio Divina uses both Stoic style meditation and Buddhist style meditation in a complementary fashion as part of a larger process.

LikeLike

labnut, it may be that to a certain extent what concerns you about Buddhist meditation is a question of terminology. Buddhism, at least in many of its manifestations including the earliest Pāli material, does spend significant time on “meditatio or reflection” in your terms. It is simply that that practice would not, or would not necessarily, be considered part of what is termed “sati” or mindfulness meditation. Many of the earliest dialogues are concerned with what we today might term logical, cognitive, or rational considerations, such as how we should go about finding worthwhile counsel (MN 95), or on the pitfalls of greed, hatred, and ignorance. One is indeed to reflect upon these matters meditatively, but with an aim towards seeing them here and now, in the present moment, rather than treating them as a cognitive puzzle that can be solved intellectually.

Since the Buddhist model of the mind does not distinguish between reason and emotion, there is no sense in Buddhism of our using reason to overcome or influence emotion. Focused practice is based on the notion that we need to spend time seeing things calmly, clearly, and directly rather than simply grasping them second-hand, as it were, based on a purely conceptual understanding.

LikeLiked by 1 person

What level of knowledge about Stoicism did participants have prior to taking part? What level would you think was necessary?

Are there plans to do this elsewhere in the world (e.g. Europe)?

LikeLike

nannus,

I don’t know of similar events in Europe (there is Stoic Week, in London in November, but that’s a different type of thing — I’ll be there, by the way).

Our participants ranged from people who were already studying Stoicism on their own to others (most, probably) who barely heard of it but were curious and intrigued by the retreat format.

LikeLike

Excellent retreat–I hope the first of many (fate permitting).

I would recommend these ancient texts to anyone. And hearing Greg and Massimo’s lessons about the readings made it clear that there are many applications to approaching modern life struggles. It worked well because I think the other participants were serious about studying and digging in deep to the readings.

Having Greg integrate some early Buddhist thinking about mindfulness and some REBT techniques was helpful. The part that struck me the most was creating a few journals with different purposes, based on how the Stoics used the philosophy. Since then, I have started keeping a journal (inspired by Marcus) in which I daily write ideas of gratefulness for my “fate,” and try to develop a way of accepting (even loving?) the traumas of the past that have led me here. It also helps me to see “preferred indifferents” as irrelevant to my eudaimonia (flourishing) as a human being.

It is a new way of seeing my history, without judgements and blame, and it makes me feel more powerful in the present moment (you know, the “hic et nunc”). Studying Stoic philosophy is rewarding, intellectually and psychologically–and it is definitely not a religion. There is no dogma, only a self-reliance and attitude of rationality. What religion would tell you to think for yourself?

LikeLiked by 4 people