Socrates teaches Alcibiades, by François-André Vincent (1776, the angel-like figure on Socrates’ shoulder is, presumably, his daimon)

Alcibiades, the ward of the famous Athenian statesman Pericles, was nineteen years old when Socrates made him cry. Alcibiades (on whom I’m seriously thinking of writing a book) was handsome and smart, and one of the most promising of Socrates’ pupils. On that occasion, however, Socrates shows him clearly just how short of virtue he is, in response to which Alcibiades weeps and begs his mentor to help him live a virtuous life. (We know from subsequent history that it didn’t work out too well.) This is the setting for the last chapter of Margaret Graver’s Stoicism and Emotion, and therefore also for the last of this series of commentaries on her book.

Alcibiades’ reaction presents an interesting structural problem for the Stoic account of emotions. Normally, Stoic theory treats emotional reactions like weeping and begging as inappropriate, because one is reacting to an object outside one’s control as if it were a genuine good. Here, though, Alcibiades’ affective response is triggered by something that is under his control (his character) and that is, in fact, the chief good (virtue, or in his case, lack thereof). So what Alcibiades is experiencing seems to come from a correct assessment of the situation, just like the eupatheiai (the positive, healthy emotions) of the wise person. And yet his response is not that of a wise person. What gives?

To get the problem, it’s helpful to think about why the wise person of Stoic theory does not ever feel remorse (for which the Greek word is metameleia):

“Remorse is distress over acts performed, that they were done in error by oneself. This is an unhappy emotion and productive of conflict. For the extent to which the remorseful person is concerned about what has happened is also the extent to which he is annoyed at himself for having caused it. … [The Stoics] hold that the person of perfect understanding does not repent, since repentance is considered to belong to false assent, as if one had misjudged before.” (Stobaeus, Ecl. 2.7.11i; 102-3W and Ecl. 2.7.11m;113W)

Remorse, then, is an affective response (“an unhappy condition”), and one that is not compatible with wisdom, because it comes from the belief that what you did was a mistake. But the non-wise (i.e., pretty much all of us) frequently do experience remorse, because we are prone to give assent to false propositions.

One can think of remorse as the judgment that “Because I acted badly, it is now appropriate for me to feel mental pain.” Is this judgment true or false? If the Stoics hold that it is necessarily false, then they need to explain what is wrong with it, since an ordinary person like Alcibiades obviously does act badly at times, and the Stoics’ own theory holds that acting badly is bad for us. Then again, if the judgment may sometimes be true, then it looks as if some forms of emotional response must actually be appropriate for non-wise people.

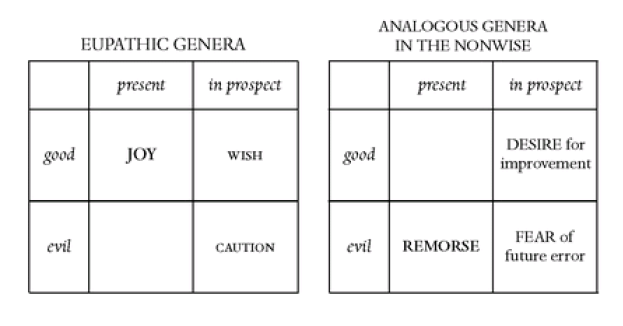

Provisionally, one could posit that just as the wise person has eupatheiai or good affective responses for present goods (e.g., a virtuous activity in the present) and also for prospective goods and evils, so also the ordinary person might have correct – but still not wise – emotional responses to present evils (her own faults) and again for prospective goods and evils, as follows:

Margaret begins the analysis by examining what she terms strategies of consolation. Consolation in times of grief was a standard philosophical practice, famously engaged in by Seneca in three letters to his friends Marcia and Polybius, and to his mother Helvia. Cicero, in his third Tusculan Disputation (at 77), contrasts two approaches to consolation by the early Stoics, Cleanthes and Chrysippus.

Cleanthes, following basic Stoic philosophy, thought that grief is the result of a mistaken judgment (that the object of grief is a true evil, rather than a dispreferred indifferent). It follows that the way to console the grieving person is to attempt to persuade him that he has made an error of evaluation. This, however, will not do, because the distressed person is unlikely to listen to that sort of argument, at least not while he is experiencing the distress. Here Chrysippus sounds eminently pragmatic:

“During the critical period of the inflammation one should not waste one’s efforts over the belief that preoccupies the person stirred by emotion, lest we ruin the cure which is opportune by lingering at the wrong moment over the refutation of the beliefs which preoccupy the mind.” (Origen, Against Celsus 8.51 (SVF 3.474), from Chrysippus, On Emotions, book 4).

Instead, Chrysippus suggests an approach to consolation that skirts the question of whether the bereavement was really an evil and concentrates on convincing the grieving person that mental pain is not, in fact, an appropriate response to evil. This looks at first like a good solution: after all, true grief has both components, a belief about value and a belief about the appropriate response, so removing either belief should work for consolation. The aim is strictly pragmatic, to get the person to calm down for now, in hopes that there may be an opportunity later on to explain why death isn’t really a bad thing.

The strategy runs into trouble, however, when it’s applied to something like remorse. Unlike the person who is weeping because someone has died, the remorseful person has a correct evaluation of the situation. Since the Stoic philosopher now agrees that something bad is present, it’s less clear why she should even be trying to eliminate the feeling of distress.

This focuses our attention squarely on the question of affective response itself. Are the Stoics only saying that the ordinary emotions are wrong because they are based on false judgments of value, or do they also mean to say that the feelings involved in emotion are just inherently wrong?

In the latter part of the chapter, Margaret isolates the specific belief-components that give rise to the feeling-laden response to a situation. These can be presented in two versions, one that applies to all forms of affective response and then a more specific version for mental pain.

[A] (general): If something which is either good or evil is either present or in prospect, it is appropriate for me to undergo some sensed psychophysical movement.

[B] (distress-specific): If an evil is present, it is appropriate for me to undergo a contraction; i.e., to experience mental pain.

Margaret’s position is that the Stoics should not categorically rule out either version, on penalty of running into inconsistencies in their philosophy. To begin with, an across-the-board denial of [A] would mean that normal affective responses are never appropriate in human beings. They would have to say that there is no right way for us to use a capacity that is inherent to human nature, a design feature of the species or (as we might say nowadays) a part of our evolutionary endowment. It really would turn Stoics into the sort of inhuman robotic caricature that they are so often (unjustly) accused of aspiring to.

What about [B], the distress-specific case? Could it be that other categories of feeling have a good use, but mental pain does not? After all, the eupatheiai or “good emotions” of the Stoic sage include forms of feeling that correspond to delight, fear, and desire, but none that corresponds to distress. Does this mean that the feeling of distress is inherently wrong?

Here I find Graver’s analysis both very clever and convincingly rooted in Stoic literature. She argues that the Stoic view is based on a counterfactual statement. The wise person would agree that IF an evil were to be present, THEN it would be appropriate to undergo a “contraction,” i.e., feeling mental pain. But of course the wise person, by definition, is never in the presence of true evil (since the only true evil is lack of virtue), and so the situation remains, for them, a hypothetical. Still, they retain the capacity for mental pain, even if they never have occasion to feel it. The ordinary person does have those occasions, both when we think we are in the presence of evil but really aren’t, and when we are in the presence of a true evil; that is, a moral evil. In the latter case, the feeling of distress is indeed appropriate.

This means that Socrates was entirely right in rebuking Alcibiades, causing in him the “biting” of shame. Indeed, the best known example of a Stoic teacher who uses Socrates’ approach is Epictetus, who often berates his students, presumably with the aim of making them ashamed of their patent lack of wisdom. The goal, of course, is not shame for its own sake, but nudging students to redouble their efforts to improve. What is being deployed here, however, is a prospective, not reactive, form of affect:

“Crucially, moral shame is a eupathic response, a species of caution rather than of fear. … Epictetus clearly holds that ordinary imperfect people have the capacity to be mortified at the prospect of justified censure for their actions in prospect. That capacity may be underdeveloped or willfully ignored, but in many, perhaps most cases it remains available to us and can assist us in choosing appropriate actions.” (p. 208)

What about apatheia, then? Remember that the pathē that Stoics wished to eliminate do correspond to some of what we today call emotions, but that not every emotion is considered a pathos, and therefore not all of them are subject to elimination. The best human condition, that of wisdom, would still have room for many strong feelings, including joy, eagerness for what is good, love, and friendship. Moreover:

“We should remember that the attainment of apatheia is not in itself the goal of personal development. For the founding Stoics the end point of progress was simply that one should come to understand the world correctly. The disappearance of the pathē comes with that changed intellectual condition: one who is in a state of knowledge does not assent to anything false, and the evaluations upon which the pathē depend really are false. … The central and indispensable point of the Stoics’ contribution in ethics and psychology [is] that no rational being wants to believe what is false.” (p. 210)

Excellent post carefully examining a difficult technical issue in Stoic theory. I think it would be great if you write about Alcibiades. At least so far as I’m concerned, he’s one of the most important characters in the ‘myth’ of Socrates, and directly related to his execution, the potential limits of philosophy, and thus a figure infinitely worth more study. If I recall properly the Platonic dialogue the Alcibiades was the one that ancient readers started with as an intro to the platonic Corpus. In so far as Stoicism uses the myth of Socrates, I think it has to have some good answers about Alcibiades and Socrates complicity or lack thereof in his education, because that question speaks to the limits of all philosophical education. Past a certain point Thucydides history really just becomes an account of the life and times of Alcibiades. If Aristotle is connected in the mythic imagination to Alexander, Socrates is to Alcibiades. For better or worse. I really think we could use a good book looking at their relationship in detail, and I think you’d be just the person to capture the nuances in a way that makes the failure of their relationship practical to a general audience today!

LikeLiked by 2 people

To understand Alcibiade, one has to understand what, and who, formed his mind. Alcibiades was the ward of Pericles. Pericles was the eloquent mouthpiece of several important philosophers, including his second wife, the philosopher Aspasia of Miletus. Some of the best philosophy ever, came out of this mouthpiece, including the theory of the Open Society (popularized by Popper). So Pericles has to be revered for those who want civilization to progress.

However, Pericles was a highly elected politician, thus a seducer, everything and its opposite. Pericles passed the xenophobic law that only men born of two Athenian parents qualified as citizens. When Athens’ demography collapsed, in a war setting, and Pericles’ own son from Aspasia, Pericles the Younger, was unqualified as a citizen, Pericles had to beg for a non-application of the law.

Thus Pericles was not a model of rigorous, emotional, or not, logic. Worse: he bet the fate of the Athenian empire on confronting Sparta and Persia, the two other superpowers. His war plan was extremely bold: let Sparta invade and try to ravage Attica, while Athens, behind its long walls connecting her to her port, would be able to get all she needed, all the way from the Black Sea, while the Spartans got bored destroying orchards. Pericles brazenly computed that Sparta could not keep a huge army long enough in the field, destroying Attica’s agriculture and olive trees, while Athenians would get their wheat from the fleet. Even after the strategy had failed dramatically, he extended it for another year (failure to learn from clear experimental evidence).

The (all too dangerous) plan collapsed when the very high density of population behind the walls, caught a “plague”. Pericles meekly had to admit his extraordinary stupidity:”I had foreseen everything, but not that.” He compounded his mistake by sending the fleet to ravage the Peloponnese… Instead, highly predictably, the fleet got ravaged by the plague. In the end, Pericles was put on trial for his lack of foresight by putting thousands of sailors into each other’s butts (it was tight in triremes!), while the plague was on board.

The overall teaching from Pericles was complete confusion (teaching the open society, passing xenophobic laws), intimate betrayal (he betrayed his second wife by making their child a non-citizen; his preceding son denounced his father), and brazen behavior, betting civilization on fumes, not just attacking Sparta and Persia, but then engaging on an insane strategy.

Exactly what Alcibiades would do with his life. Alcibiades was all too much Pericles’ spiritual son.

LikeLike

Patrice,

this is interesting, but I’m in no position to judge whether your portrait of Pericles is on track. I doubt it is, frankly. Do you have sources for this?

LikeLiked by 2 people

It will be interesting to see if any of your readers have comments that are not just about Alcibiades.

LikeLiked by 3 people

Alcibiades is just too fascinating a figure to not get caught up in!

LikeLiked by 2 people

As I read and contemplate Stoic thought and Philosophy Icant but help as deal with old Lessons learned. Take how would Stoic Philosophers approach ,say Dylan Thomas Well know Do Not Go Gentle Into That Good Night .Would they trivialize it ? Is there a place for this? ..What is the takeaway on the Poets attempt to give meaning in the mind of Stoics?

LikeLike

I really like “We should remember that the attainment of apatheia is not in itself the goal of personal development. For the founding Stoics the end point of progress was simply that one should come to understand the world correctly.”

There have been many people who try to attain apatheia in life, maybe with the purpose of escaping the world that is filled with unjust and suffering. However, many of them just simply become “don’t see, don’t think, don’t care”.

LikeLike

I like the final excerpt as well, but I also find it puzzling, in a Stoic setting. To state that the highest aim is epistemological, rather than ethical, is not what I am accustomed to hear from the Stoics.

“For the founding Stoics the end point of progress was simply that one should come to understand the world correctly”

This sounds rather more Aristotelian.. and

“The central and indispensable point of the Stoics’ contribution in ethics and psychology [is] that no rational being wants to believe what is false.”

sound more as a moto of the Skeptics, rather than of the Stoics..

LikeLike

Ram,

I had similar thoughts myself, but upon reflection I think Margaret is exactly right. Where do the Stoics get the idea that virtue is the highest good? From their observation of the world, hence the preliminary importance of physics for the ethics. And no, the skeptics did not believe that it was possible to believe something one would know to be true.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Massimo, even so, it would follow that physics, or understanding the world is a crucial starting point (Socrates, by the way, denied it). But Margaret seems to be asserting something else. She says that understanding the world is not the start, but the end: “the end point of progress”…

LikeLike

Yes, that seems reasonable. Hopefully Margaret will chime in, now that we are no longer talking about Alcibiades!

LikeLike

Let’s let Seneca say it, in the 92nd Letter:

“The happy life consists solely in perfecting our rationality … What is a happy life? It is security and lasting tranquility, the sources of which are a great spirit and a steady determination to abide by a good decision. How does one arrive at these things? By perceiving the truth in all its completeness, by maintaining orderliness, measure, and propriety in one’s actions, by having a will that is always well-intentioned and generous, focused on rationality and never deviating from it.”

Ram, understanding the world is exactly what Stoicism is about — both in its ancient version, which I study, and in any modern version that is worthy of the name. That is a very difficult goal, far more difficult than your post seems to assume: it means sifting through all your beliefs and also correcting your very process of forming beliefs, with no tolerance for error. But that is the natural goal for the human being, because being human means, precisely, being the sort of creature that thinks and judges.

Because you mention Aristotle in this context, I am guessing that your worry is about theory as opposed to practice. Aristotle separates the intellectual virtues from the practical virtues, the ones that involve action, also called the moral virtues. That’s not how it is for the Stoics. For them, as for Socrates, action is fully determined by the judgments and choices that you make, with the result that once you get the world right, you also get your judgments right of how to act and yes, also how to feel. Ultimately, knowledge and virtue are one and the same thing.

You are quite right to bring in physics — in its ancient sense, that is closer to what we mean by “the natural sciences,” including psychology and theology (since in Stoicism both god and the psyche are fully natural phenomena). It’s not assumed that even the person of perfect wisdom would know these studies in their entirety, but taking them seriously, both the actual facts they have to offer and the rational principles by which they proceed, is necessary not only for our intellectual development but also for our moral development.

As a starting point, or an endpoint? There seems to have been some debate among the ancient Stoics as to which area the student of philosophy should explore first — physics, ethics, or logic. The one thing they were clear on, though, is that the three areas form one whole. Like an egg: logic is the shell, ethics the white, and physics the yolk. The point is not which part is which; it’s that the three are interrelated.

LikeLiked by 3 people

I’m not sure that Pericles deserves to be quite so roundly condemned. Part of the problem of any reasoned judgement about him is that our main source, Thucydides, seems to have been a strong supporter, contrasting him favourably with the more demagogic politicians. This may partly be due to the involvement of the latter in Thucydides’ exile. Having said that, while Pericles’ might have had an elevated view of Athens’ greatness (the Funeral Oration is an extended ode to “Athenian Exceptionalism”) and perhaps been over-confident, the fact remains that the first part of the Peloponnesian War (or the First Peloponnesian War if you don’t follow the Thucydidean convention that there was only one conflict) ends in a score draw, which contrasts sharply to the expectations at the start where Sparta is expected to secure an easy victory. If wars end when both sides have an accurate view of their relative power, Pericles’ strategy was pretty successful. It is only when the Athenians later get too cocky and invade Sicily (by which time Pericles was long dead) that the problems arise.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Massimo,

If I may briefly change the subject. I saw on Twitter you are giving the platform address at the Ethical Society of St. Louis today. For years, I’ve listened to the Ethical Society of St. Louis’ podcast. Every August, Kate Lovelady compares Ethical Humanism, aka Ethical Culture, to other traditions. She gave a platform address comparing Ethical Humanism to Stoicism. A couple of years ago, she compared Ethical Humanism to Stoicism. I recall her speaking favorably of Stoicism. (I can’t find that episode, but I’ll keep looking.)

LikeLike

Leonids,

thanks for the comment. Indeed, I’m about to go there in a couple of hours. I will be talking about science vs pseudoscience, though, not Stoicism. Last night I have a talk at the local Skeptics in the Pub, on virtue epistemology.

LikeLike

Stewart:

I do agree with some of what you say. Yet, Aspasia wrote the Oraison (that’s a fantastic set of ideas, which Pericles himself lauded and then contradicted with his xenophobic laws). However, the Sicilian disaster, launched by Alcibiades, is more of the same, as far as the mood was concerned: bet everything on a chancy military adventure (as in the six years war in Egypt, coincident apparently with war with Sparta!)

The incoherence and extreme boldness, not to say foolhardiness, of policies endorsed by Pericles, contrasted strikingly with the caution of, say, Themistocles. Unbelievably, it was part of Pericles’ strategy that the Spartan field army, and its numerous allies, would invade Attica every year. His meek “I didn’t think about that” is thoroughly inappropriate. He was talking about the plague, but clearly he didn’t think about what a yearly invasion of Attica would be (the strategos at the time of Marathon thought about it, and, after the Marathon battle, the victorious Athenian field army marched ASAP to Athens, to prevent a landing of the Persian fleet there).

LikeLike

I found a link to that Ethical Society of St. Louis podcast episode, “Ethical Humanism and Greek Philosophy,” recorded August 30, 2015. Kate Lovelady begins by referencing William Irvine’s “A Guide to the Good Life.”

LikeLiked by 1 person

Okay people, I suggest we go back to Stoicism. History is interesting, but this blog isn’t devoted to the Peloponnesian war…

LikeLiked by 2 people

A link to Kate Lovelady’s August 30, 2015, address “Ethical Humanism and Greek Philosophy” is online at https://ethicalstl.org/ethical-humanism-and-greek-philosophy-kate-lovelady-leader/ She starts talking about Stoicism around 9 minutes into the talk, not quite at the beginning as I said in my above post.

LikeLike

You’re welcome, Massimo. I should have noted I was aware that you are talking about science vs psuedoscience. But if you find yourself speaking with Kate Lovelady after the address, she might ask you about Stoicism. I’m listening to her August 2015 address. Unfortunately, she likens ancient Stoics to Vulcans, but otherwise she seems to have a good grasp of Stoicism. She recommends to the audience they practice voluntary deprivation because it reflects Ethical Humanist values.

LikeLike

Here’s that link to Kate Lovelady’s August 30, 2015 talk. (Readers note I’m not trying to promote Ethical Humanism. I remember when I listened to the podcast, I was struck by how Lovelady recommended some aspects of Stoicism as a way to become more virtuous — to an audience so committed to ethics they joined a tradition with the word “ethical” in its title. https://ethicalstl.org/ethical-humanism-and-greek-philosophy-kate-lovelady-leader/)

LikeLike

Margaret,

I think it is an interesting question, how much “understanding of the world” a Stoic would actually need, or desire. Here is probably not the place to pursue this further.. Kudos for your thorough work, and to Massimo for this thorough review.

LikeLiked by 1 person