[Feel free to submit a question for this column, but please consider that it has become very popular and there now is a backlog, it may take me some time to get to yours.]

[Feel free to submit a question for this column, but please consider that it has become very popular and there now is a backlog, it may take me some time to get to yours.]

D. writes: “How would a Stoic react to our modern concept of IQ and genetics? In societies where high-IQ is correlated with achieving academic accomplishment in high-level subjects, and the corollary benefits conferred to them by society, what would a Stoic do in the face of this genetic determinism? What would a Stoic tell someone who had low intelligence, but desperately wanted to achieve competence in a high-level skill? A life pursuing your dream, even in inevitable and constant failure is more meaningful than a life where a dream is given up? Or, would he be advised to live a more practical life? Did the Stoics have a concept of innate talent?”

Very good question, and — if I may be a bit immodest — you asked the right person, since I’m not just a practitioner of Stoicism, I’m a biologist whose specialty happens to be gene-environment interactions.

So let me first start with a bit of scientific background. As you know, the Stoics thought it important to study not just “ethics” (by which they meant the way to live one’s life) but also physics (which included natural science). That is because one cannot navigate the world effectively if one doesn’t have a decent idea of how the world actually works. So a basic knowledge of science is very much relevant to how the Stoic approaches ethical questions.

Both the concept of heritability and that of IQ are fraught with controversy. And I don’t mean just the political-ideological ones. Yes, it is true that the left tends to reject any talk of IQ and heritability because it sees it as undermining human freedom, just as it is true that the right typically embraces it in order to maintain what they prefer, the societal status quo. I’m talking about scientific controversies. A good summary of the main issues is found in this essay by my friend and colleague Jonathan Kaplan, and much more is in my book, Phenotypic Plasticity: Beyond Nature and Nurture.

The bottom line, however, is this:

i) IQ measures a highly culturally influenced portion of analytic “intelligence” (however one wishes to define the latter term), and accordingly the result of the test varies with age, level of instruction, and method of delivery. This isn’t to say that the test doesn’t measure anything worth measuring, but that whatever it measures boils down to a rather simplistic single number that leaves out a lot of pertinent complexity.

ii) Heritability does not, I repeat not, measure the degree of genetic determination of a trait. To begin with, heritability is a statistical measure that only makes sense at the level of a population, not an individual. So when we say that, for instance, human height has a heritability of 80%, this does not mean that 80% of my height is the result of genes and 20% of environmental influences. Rather, it means that 80% of the so-called phenotypic variation in height in a given human population statistically correlates with genetic variation in that population. To understand why this isn’t the same as genetic determinism, consider the following simple example: the heritability of number of nostrils in humans is zero, because there is basically no variation for that trait in our species (we all have two nostrils). Yet the trait is, as it turns out, very strongly genetically determined: there is no environment in which we develop one or three or any number of nostrils other than two.

iii) Contra popular misunderstanding, heritability is a local, not general, measure, meaning that it varies with the specific genetic makeup of a population, as well as with the environment in which individuals grow up. Which in turn means that it makes no sense to say that the heritability of IQ is x. Rather, we should say that the heritability of IQ for this particular population and in this particular range of environments is x. Change either the genetic make-up of the population, or the environment, and you get a different number. Sometimes a radically different number.

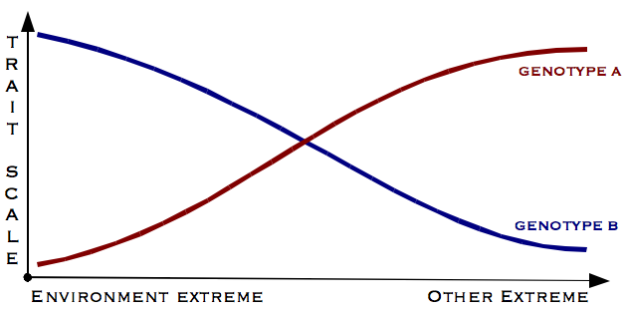

iv) Moreover, what really matters is not the single number given by the heritability (at a population level), but rather a series of individual (for each of us) functions relating phenotype (in this case, IQ), genotype, and environment by way of what is called a norm of reaction. A norm of reaction is a genotype-specific curve that looks like this:

Knowledge of the set of reaction norms in a population of organisms tells us precisely how the genetic make-up of those organisms interacts with the range of environments likely to be encountered by those organisms, yielding a corresponding range of phenotypes. This genotype-environment interactivity manifests itself in the phenomenon known as phenotypic plasticity, the fact that whenever reaction norms are not flat (i.e., not parallel to the environmental axis) the expressed phenotype for a given genotype will be a function of the environment.

v) Lastly, in terms of scientific background, it turns out that it is next to impossible to measure reaction norms in humans, for the simple reason that we cannot clone people and grow them under controlled conditions (there are both logistical and obvious ethical issues precluding it). So we can only indirectly guess at the degree of plasticity of a given trait. In the case of IQ, we know that it is plastic (because it is affected by early development, availability of material resources, education, and so forth), but we don’t know how much, or the variability in plasticity in the human species.

Sorry to go on for so long on this, but as I said — from a strictly Stoic perspective — getting the science right is necessary. Now, with the above background firmly in mind, let me get more specifically to your questions.

Since we do not know the degree of genetic determinism of IQ (as I said, it isn’t measured by heritability), in some sense your first questions are pre-emptied. The Stoic shouldn’t do anything about IQ and genetics for the simple reason that we don’t know much about it. There is no actionable knowledge to go by.

I hasten to say that the Stoics themselves were, in fact, both materialists and determinists: they believed in universal cause and effect. People tend to forget that our genetics isn’t the only thing that contributes to determine our lives. Environmental influences are also deterministic, and so are the (complex, very hard to measure) gene-environmental interactions jointly captured by the ideas of plasticity and norms of reaction. So in some sense the question is ill posed from a Stoic standpoint: regardless of whether it is genes, environments, or (much more realistically) both, our lives are determined anyway.

[This often, and mistakenly, leads people to some sort of nihilism. I will address the Stoic response to that reaction — known as the “lazy argument,” later this week.]

However one’s intelligence comes about, your further questions still apply. What would a Stoic tell someone who had low intelligence, but desperately wanted to achieve competence in a high-level skill? Is a life pursuing your dream, even in inevitable and constant failure, more meaningful than a life where a dream is given up?

Let me start by saying that a Stoic wouldn’t say anything to anyone, unless explicitly asked (as you are doing with me). Stoicism is not supposed to be brandished as a stick to beat other people over the had. It is first and foremost for our own personal improvement.

However, assuming someone did ask you for advice, the first response as a Stoic would be that the only life worth pursuing is one of moral excellence, achieved by practicing the virtues. And that has nothing to do with what sort of job one happens to be doing, which falls under the category of preferred indifferents. Here is Seneca on the topic:

“Virtue is not changed by the matter with which it deals; if the matter is hard and stubborn, it does not make the virtue worse; if pleasant and joyous, it does not make it better. … Come now, contrast a good man who is rolling in wealth with a man who has nothing, except that in himself he has all things; they will be equally good, though they experience unequal fortune.” (Letter LXVI. On Various Aspects of Virtue, 15 & 22)

Change “wealth” and “fortune” with “profession” and “IQ” and the sentiment is the same.

Second, Stoics were very practical people: if something turns out to be unachievable, then it is foolish to keep dreaming about it. You ought instead to take stock and focus on the sort of thing you can do and make the best of them.

I may dream of being a soccer star. But I’m not built for it, I have no talent for it, and I didn’t begin training early enough in my life. It would be silly of me to keep dreaming about it while neglecting my actual profession, perhaps putting my family in danger of poverty as a byproduct of my dreaming. The same applies to wanting to be an actor, a musician, a writer, or a Wall Street banker (though I must admit the latter to be the furthest away from my dreams).

I hasten to say, however, that this isn’t a counsel for resignation in the face of adversity. Even well before I became a Stoic I was determined to pursue an academic career. I knew this was next to impossible in Italy, where I grew up, because of the chronic dearth of funding and even more so the cancerous level of nepotism in the academy. So I left and moved to the United States, where a combination of luck, determination, and some skill allowed me to become what I dreamed of becoming.

Had I had the benefit of Stoicism early on I would have done exactly the same, but my attitude would have been healthier. Just as in the case of the famous archer in Cicero’s De Finibus, becoming a university professor would have been “chosen but not desired,” because my decision to pursuit that career, and the efforts I made, were up to me; but the ultimate outcome wasn’t:

“If a man were to make it his purpose to take a true aim with a spear or arrow at some mark, his ultimate end, corresponding to the ultimate good as we pronounce it, would be to do all he could to aim straight: the man in this illustration would have to do everything to aim straight, yet, although he did everything to attain his purpose, his ‘ultimate End,’ so to speak, would be what corresponded to what we call the Chief Good in the conduct of life, whereas the actual hitting of the mark would be in our phrase ‘to be chosen’ but not ‘to be desired.'” (Cicero, De Finibus Bonorum et Malorum, book III, 22)

Massimo,

Thank you for leaving Italy. Apart from the Stoic advice that is the single best paragraph on heritability (ii) that I have seen – anywhere. Great work.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Salve Massimo,

trovo molto interessanti i suoi commenti sullo Stoicismo. Se posso darle un consiglio, dato che il tema sta crescendo enormemente in North America, pubblicherei questi articoli anche su Medium. E’ una piatttaforma blog social di grande successo, collegata a Twitter e a tematiche precise. Buona giornata

Andrew Berselli

LikeLiked by 1 person

Probably doesn’t take away from your point, but isn’t heritability of nostrils undefined, and not 0? That’s because the variance of the phenotype, which is in the denominator of the heritability calculation, is 0?

LikeLike

Dr Pigliucci,

D, here. Thank you so very much for that thorough response- it exceeded all expectations. As someone who has spent a lot of time thinking about this, you’ve given me some novel insight and a new route of thinking to pursue (including the supplementary resources you included). Again, much appreciated.

LikeLike

Cmp,

Yes, technically the heritability is undefined, unless there is a minimum amount of phenotypic variation (e.g., from developmental anomalies, which do occur, rarely), in which case the denominator of the ratio defining the heritability is non-zero. But as you say, the point stands.

Logo,

I’m glad you found the comments useful, and thanks for submitting your question!

LikeLike

Buongiorno, ho apprezzato molto questo suo articolo e chiedo la sua autorizzazione a tradurlo (a meno che non sia già disponibile in italiano) e condividerlo. Cordialmente, Paola

LikeLiked by 1 person

Paola,

Assolutamente. Per cortesia fammi sapere se/dove viene pubblicato, potrò aiutarne la diffusione usando il mio network di Twitter.

LikeLike

http://www.inseparatasede.com

LikeLiked by 1 person

I should also add that intelligence, even more accurately measured, is not a good measure of success even in academia, considering all the idiots I’ve had the misfortune to run into over the years, who were even in a position of authority.

LikeLike

My favorite book questioning how we define intelligence was “IQ: A Smart History of a Failed Idea” by Stephen Murdoch. According to him, what IQ measures is a type of abstract problem-solving ability that develops as a result of the types of schooling done in modern industrialized societies under ideal conditions of nutrition, education, and probably also encouragement to study, and is thus far from a direct measure of raw neurological capacity to learn any and all things. In other words, as the old saying goes, “a standardized test measures how good you are at taking standardized tests.” Those who ace standardized tests and still do their jobs poorly are likely lacking in some sort of practical wisdom.

LikeLike