On this blog, I don’t like to write about either politics (but here is an example) or religion (example here), because one of the main attractions of Stoicism, for me, is precisely that it is a big tent in both those areas: one can be a virtuous conservative or progressive, and similarly one can be religious or atheist and still practice the four cardinal virtues. When I do talk about these topics, it is only from a broad Stoic perspective, and making a very conscious effort to respect other people’s opinions. That said, of course, to welcome a variety of opinions under the same tent does not mean that one doesn’t have one’s own opinion, nor does it mean that one thinks all points of view are equally valid. It is therefore with great reluctance that I take up the topic of climate change which, while technically a scientific issue, has in fact become a highly divisive ideological one. But a fellow Stoic asked me to weigh in, partly because I am a scientist and philosopher of science, and therefore more acquainted with the details than many. So here we go.

On this blog, I don’t like to write about either politics (but here is an example) or religion (example here), because one of the main attractions of Stoicism, for me, is precisely that it is a big tent in both those areas: one can be a virtuous conservative or progressive, and similarly one can be religious or atheist and still practice the four cardinal virtues. When I do talk about these topics, it is only from a broad Stoic perspective, and making a very conscious effort to respect other people’s opinions. That said, of course, to welcome a variety of opinions under the same tent does not mean that one doesn’t have one’s own opinion, nor does it mean that one thinks all points of view are equally valid. It is therefore with great reluctance that I take up the topic of climate change which, while technically a scientific issue, has in fact become a highly divisive ideological one. But a fellow Stoic asked me to weigh in, partly because I am a scientist and philosopher of science, and therefore more acquainted with the details than many. So here we go.

To begin with, I will actually not present any detailed technical argument in favor of the notion of anthropogenic climate change (which I must state for full disclosure, I accept). There are several reasons for it, including: i) there are very, very good and accessible treatments of the matter already out there; ii) even though I’m a scientist, I’m not an atmospheric physicist, so it isn’t clear why my opinion on the technical matter should carry particular weight; and iii) this is a blog about Stoicism, not science per se.

Nevertheless, how should a Stoic tackle the issue of climate change, for instance in terms of deciding how to vote in an election where some candidates accept the notion and would push for legislation to address it, while other candidates reject it and would therefore oppose any such legislation?

We need to go back to the basics, and specifically to the relationship among the three fields of logic, physics, and ethics, and also reconsider the Stoic concept of cosmopolitanism.

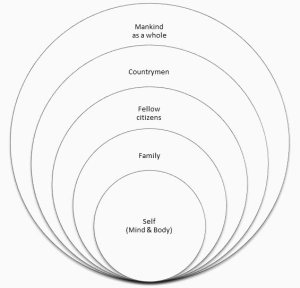

Let me start with the latter. As I explained previously, the second century Stoic Hierocles summarized the concept of cosmopolitanism (which the Stoics inherited from the Cynics) by saying:

“Each of us is, as it were, [is] circumscribed by many circles; some of which are less, but others larger, and some comprehend, but others are comprehended, according to the different and unequal habitudes with respect to each other. For the first, indeed, and most proximate circle is that which everyone describes about his own mind as a centre, in which circle the body, and whatever is assumed for the sake of the body, are comprehended … The second from this, and which is at a greater distance from the centre, but comprehends the first circle, is that in which parents, brothers, wife, and children are arranged. The third circle from the centre is that which contains uncles and aunts, grandfathers and grandmothers, and the children of brothers and sisters … Next to this is that which contains the common people, then that which comprehends those of the same tribe, afterwards that which contains the citizens; and then two other circles follow, one being the circle of those that dwell in the vicinity of the city, and the other, of those of the same province. But the outermost and greatest circle, and which comprehends all the other circles, is that of the whole human race … it is the province of him who strives to conduct himself properly in each of these connections to collect, in a certain respect, the circles, as it were, to one centre, and always to endeavour earnestly to transfer himself from the comprehending circles to the several particulars which they comprehend.”

To put it simply: we ought to give a crap about everyone on earth, from our close kin and friends to complete strangers on the other side of the globe.

Hierocles’ circles of concern

To me this clearly implies that if we have good reasons to believe that the earth’s climate is changing for the worst as a result of our own actions, then we have a moral duty to intervene. I hope that even those people who reject the premise would readily agree with the conditional itself.

But of course the crucial question is: do we have such reasons? How would a Stoic go about determining that? That’s where the interrelationship among logic, physics, and ethics comes into play.

It is for a very good reason that the Stoic curriculum included the three fields, as Diogenes Laertius reminded us: “[the Stoics] liken Philosophy to a fertile field: Logic being the encircling fence, Ethics the crop, Physics the soil or the trees.” (Lives of the Eminent Philosophers, Book VII)

Logic was the study of sound reasoning, which was broader than the modern meaning of the word “logic,” as it included also epistemology (i.e., a theory of knowledge), what we would today call cognitive science, and even rhetoric (the art of persuading others to accept certain ideas). In terms of the topic at hand, then, we need to make sure that we are reasoning correctly, which means first and foremost to engage in a serious analysis of our own biases and potentially logically fallacious reasoning.

And speaking of logical fallacies, one thing that I have often seen come up in the context of discussions of climate change, is the frequent throwing around of accusations of engaging in so-called informal logical fallacies. For instance, someone who denies the notion of anthropogenic climate change may try to deflect the criticism that it is the oil and coal industries that are most vehemently opposed to it by charging their opponents of committing a genetic fallacy: dismissing an argument on the sole basis of the character or interests of whoever is advancing it. Just because the oil and coal industries have a vested interest in keeping things as they are, the argument goes, it doesn’t mean that their criticism of climate change research ought to be dismissed out of hand.

This is certainly true, as far as it goes, but the genetic fallacy — like almost all informal logical fallacies — may in some cases actually embody perfectly acceptable reasoning based on pragmatic heuristics. For instance, it is in general a good idea to at the least be skeptical of someone’s arguments if it turns out that that someone has a personal stake in the matter under debate. If you know that a person has something to gain financially, say, from a given transaction, you will be well served to be cautious before accepting his “disinterested” advice. So while invoking the genetic fallacy does serve the purpose of reminding one’s opponent that industry positions cannot be automatically ignored, it is also true that it is perfectly reasonable to be at the least somewhat suspicious of those positions.

Another example would be that of a proponent of climate change who says something along the lines of “NASA accepts the notion, and that’s good enough for me.” He is opening himself to a charge of argument from authority. And it is certainly the case that, ideally, we shouldn’t accept something only because someone in position of authority (real or imagined) said it. But it is nonetheless true that NASA is a professional organization employing lots of people who understand atmospheric physics much better than you or I do, so it is rational to give their opinion more weight than our own or that of unqualified third parties. This isn’t earth shattering logic: it is precisely what you do when you bring your car to a mechanic, or entrust your teeth to a dentist. You assume, reasonably, that people who specialize in car mechanics or dentistry are a better — while certainly not infallible — choice than a random guy from the street.

(For interested readers, I co-wrote a paper on this kind of misuse of informal logical fallacies.)

Let’s move on to the relevance of studying Stoic physics. That term was, of course, much more comprehensive than it is today, including all the natural sciences as well as metaphysics. The Stoics thought that in order to know how to live a eudaimonic life (the object of study of their ethics) one has not only to make sure that one’s “ruling faculty” works properly (see logic), but also that one has the best possible understanding of the way the world works.

The problem, in the case of climate change, is that most people simply don’t have the necessary technical knowledge to truly follow the debate on a high level. Even so, at the very least, and regardless of whether you accept or reject the notion of climate change, if you wish to engage in discussions about it, you should try to do some reasonable amount of homework and get a grasp of the basic concepts of atmospheric science, the mechanics of the greenhouse effect, and the purported reasons why so many scientists think anthropogenic climate change is a reality. If you cannot clearly explain these concepts to someone else, then I suggest you do not have a sufficient command of the basic issues, and should therefore abstain from engaging in discussions — on one side or the other.

The latter situation will likely apply to most people. We conduct busy lives, and atmospheric physics isn’t exactly easy to assimilate. And even if we do assimilate an elementary version of it, that still doesn’t put us on a par with actual experts. Then what? To help out the presumably many people who find themselves in this situation, here is an excerpt from a paper soon to be published in the journal Theoria that I co-authored with Stefaan Blancke and Maarten Boudry, from the section entitled “Distinguishing experts from non-experts”:

“Alvin Goldman has argued that, even though novices or lay people do not have epistemic access to a particular domain of knowledge, they can rely on five sources of evidence to find out which experts they can trust. Firstly, one can check the arguments that experts bring to the discussion. Lay people may not be able to grasp the arguments directly, but they can check for what Goldman calls ‘dialectical superiority.’ This does not simply mean that one looks for the best debater – although debating skills can certainly add to the impression that one is an expert – but that one keeps track of the extent to which an alleged expert is capable of debunking or rebutting the opponent’s claims. Secondly, a novice can check whether and to what extent other experts in that field support a given (alleged) expert’s propositions. It will be more reasonable to follow an expert’s opinion if it is in line with the consensus. Thirdly, lay people can distinguish between experts on the basis of meta-expertise, in the form of credentials such as diplomas and work experience. For example, an expert with a PhD in a relevant field can in general be considered to be more reliable – ceteris paribus – than an amateur. Fourthly, a novice can check for biases and interests that affect an expert’s judgement. If an expert has a stake in defending a particular position, it will raise the suspicion that he is not interested in providing correct information, which will undermine his credibility. Of course, nobody can be free of biases, which also counts for scientists. Hence, the question is not whether there is bias (there always is), but how much, where it comes from, and how one can become aware of and correct it. Fifthly, a novice can assess an expert’s past track record. The more an expert has been right in the past, the more he has demonstrated that he has indeed access to some expert domain. As such, he will probably be right again in the future.”

(A link to the full paper by Goldman is here.)

So to recap, here is what a good Stoic would do about the issue of climate change:

1. Logic: make sure you have a basic understanding of formal and informal logical reasoning, paying particular attention to the fact, explained above, that so-called informal logical fallacies sometimes are not fallacious at all, so that you can’t simply mindlessly invoke them to shut down those who disagree with you.

2. Physics: make sure you have a good technical understanding of the issue, if possible. If not, try to at the least work your way up to the level of a reasonably well-informed novice. Unless you are an expert, though, seriously consider implementing Goldman’s guide to the five sources of evidence for how to judge reliable expertise.

3. Ethics: reflect on the meaning of the virtue of justice, as well as on the Stoic concept of cosmopolitanism and on the specific approach suggested by Hierocles. Use these tools to seriously ponder what the best thing to do would be for humanity at large.

4. Take a position in good conscience, based on the best reasoning and evidence that is available to you.

“I hope that even those people who reject the premise would readily agree with the conditional itself.” Based on the views of the right-wing religious side of my family, I would say that is a vain hope, Massimo. They see their moral duty as allowing God to end the world whenever He wants, and they look forward to it happening soon. Convincing such people to accept man-made climate change and then to do something about it is not easy. After all, they voted for Trump. I am really not looking forward to this year’s Thanksgiving dinner. )-;

LikeLiked by 3 people

Climate change is a relatively easy case. The argument, like the atmosphere, is transparent to light but not to heat. The standard model has demonstrated its predictive value, and the contortions of those who deny the science are obvious.

But how to cope with questions such as taxation policy, immigration, or free trade, where the issues are enormously complex, and experts either inaccessible, or, like academic economists and professional financial advisers, discredited? How, indeed, to set about to evaluating proposed responses to climate change? For example, the extent to which we can rely on renewables is a highly technical matter. I am unequipped to decide between competing claims, and it would take weeks of work to remedy this.

LikeLiked by 2 people

By nature Irish people are stoic, understandably it has been required over the years. A sense of humour and the occasional pint of Guinness also help everyone to integrate and respect each other’s beliefs. Massimo, f all could learn from your Stoicism, the universe’s future could indeed look brighter. Not always easy though when God has more influence:-

http://www.independent.ie/irish-news/politics/story-of-noahs-ark-is-proof-that-climate-change-does-not-exist-danny-healyrae-34975388.html

LikeLike

Pingback: Stoicism and climate change | How to Be a Stoic – The <SPB>

Paul,

You are right, what to do in response to climate change is much more complicated an issue than looking at the evidence pro/against the very notion. Which is why it would be virtuous to be even more agnostic about it, letting a diverse group of scientists, economists and policy makers talk it out and see what they come up with.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Excellent piece: thanks once again!

LikeLiked by 2 people

Regarding the very complex issues introduced by Paul and the idea proposed by Massimo, I’d like to underline that in a case like that every member of this board (but in general, every scientist, economist, ecc. ecc.) should have a totally laic point of view. A scientist can be a religious person for sure, but when he works on his research he must put in brackets those spiritual beliefs, otherwise he risks compromising his studies.

Oh, and great piece by the way.

LikeLiked by 1 person

https://goo.gl/Hwv4vw

The basic physics of global warming is very simple. It is laid out in above note. It is based on a homework problem I had in a course on planetary science at NASA summer school at Columbia in the summer of 1967. The basic energy balance that controls temperature and, indeed makes life possible are, is very simple. You need not be a climate scientist to follow it And it shows that order-of-magnitude we are doing something big enough to drive temperatures up too much, too fast.

You don’t have to believe in the detailed predictions of complex models to understand that we are doing an experiment on our climate that is likely to cause disastrous effects.

We should NOT do this experiment, but with the election of Trump is appears likely we are..

-Traruh

LikeLike

This is an admirable essay and I particularly like the five steps for “Distinguishing experts from non-experts”. I have written them down as a guideline for myself. I also like your points about big tent thinking and cosmopolitanism, which really deserves another essay.

But regrettably I must say that I think you are addressing the wrong issue. The five steps you outline are carried out by very few people and in fact can only be carried out by a few motivated people with privileged access to information.

What you have described is an epistemic process whereas, for most people, knowledge is acquired through a social process. Knowledge migrates through the social web from authoritative sources through many nodes in the web to the endpoints. This social, migratory process determines whether the knowledge is acceptable. During the migratory process the knowledge is filtered, distorted and coloured by emotional biases. More often than not, the emotional biases that become attached to the knowledged determines its acceptability.

The key word here is acceptability and not truth. The person, on receiving the knowledge, makes a final determination whether the knowledge is acceptable. This is an emotional decision that depends on:

1) influence of nearby nodes with high status

2) fit to the agent’s belief system

3) compliance with the beliefs of neighbouring nodes

4) agent’s assessment of the bona fides of the source.

5) the emotional colour of the information.

Now truth should outweigh these considerations but it never does. This is as much true of the liberal world as it is true of the conservative world. It is simply human nature that we attach great credibility to information from our immediate tribe and that information always passes through an emotional filter.

If we wish to gain acceptance for the climate change message(and we must), we have to attend to the social process far more than we do to the epistemic process. And here the liberal world has gone horribly wrong. It subjects the conservative world to intense criticism(yes, I know they respond in kind) for their religious beliefs, their ethical beliefs and their social beliefs. That is a very satisfying thing to do and schadenfreude is very pleasurable. But it creates hostility that jeopardises our attempts to gain acceptance of important truths. They question our bona fides, become deeply suspicious of our intentions and so distrust information coming from us.

And then we blame them for rejecting our message. Now that’s logical.

None of my large projects would ever have gained approval if I had made a practice of attacking the beliefs, values and aspirations of our Board of Directors. Their emotions could be depended upon to override their judgement and these are capable, intelligent, well informed people.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Ali,

“the occasional pint of Guinness also help ”

and a regular pint of Guinness helps even more. There is no ‘golden’ mean where Guinness is concerned 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Labnut,

While I agree with your basic points, it is hardly fair to say that the left has gone horribly wrong and has mounted an insult attack on the right. Setting aside the vocal minority of new atheists, that has not been the case at all, either in the US or in Europe.

What has happened, instead, is a vigorous attack on progressivism by the extreme right, based on self-righteous indignation, hurling of insults, and so forth (including several acts of violence).

Both sides need to calm down and reason their way to whatever common ground they may have.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Massimo,

“While I agree with your basic points, it is hardly fair to say that the left has gone horribly wrong and has mounted an insult attack on the right”

Well, I am an un-American and therefore ignorant of and tone deaf towards the finer points of American politics, which makes me open to criticism. Add to that my occasional tendency towards over-statement and then I deserve the criticism 🙂

Yes, the culture wars have been escalating to the crescendo of mutual recrimination and so I agree with you that

“Both sides need to calm down and reason their way to whatever common ground they may have.”

The only people with the power to make that happen are the leadership. They set the tone, expectations and example. They can rein in unacceptable behaviour and encourage the right kind of behaviour. But is that possible given the combative nature of today’s politics?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Cosmopolitanism

“To put it simply: we ought to give a crap about everyone on earth, from our close kin and friends to complete strangers on the other side of the globe.”

Why?

You have stated an ought without any clear grounding. The ancient Stoics had a clear reason(the shared divine breath), but you, as an atheist, must needs find an alternative reason. What is that reason? What makes it compelling?

LikeLike

Cosmopolitanism

“To put it simply: we ought to give a crap about everyone on earth, from our close kin and friends to complete strangers on the other side of the globe.”

Why?

You have stated an ought without any clear grounding. The ancient Stoics had a clear reason(the shared divine breath), but you, as an atheist, must needs find an alternative reason. What is that reason? What makes it compelling?

LikeLike

Cosmopolitanism

“To put it simply: we ought to give a crap about everyone on earth, from our close kin and friends to complete strangers on the other side of the globe.”

Why?

You have stated an ought without any clear grounding. I agree we ought to give a crap but I have a very clear reason. What is yours? Is it defensible or merely a wish? The ancient Stoics had a clear reason(the shared divine breath), but you, as an atheist, must needs find an alternative reason. What is that reason? What makes it compelling?

LikeLike

Sorry about the repetitive posting. I got a ‘server down’ message and every retry resulted in a new posting but that was not visible to me.

LikeLike

Labnut,

I get it from the same place the Stoics did, which wasn’t the divine breadth (that in itself says nothing about cosmopolitanism), but rather their theory of oikeiosis, or moral development: http://tinyurl.com/ho4btfn

LikeLike

Click to access climateletter.pdf

A sensible note on the implications of uncertainty for our response to global warming.

Just the opposite of what my wife heard Dixy Lee Ray say at the Hoover Institutio some time around 1987. My response at the time when the climatic model uncertainties where larger than today was that she had gotten it backwards.

Uncertainty ==> Don’t do the experiment.

LikeLike

Massimo, thanks for that reply.

In general I support Stoic cosmopolitanism but I am looking for a rationale independent of my theistic beliefs. This is my first attempt at understanding, using arguments from introspection, from virtue and from reciprocity.

A. The premises.

A.1. I am a conscious, rational person capable of introspection.

A.2. Through introspection I have identified certain social needs(for justice, compassion, liberty, mercy, etc) that are vital to me.

A.3. I expect that others treat me accordingly.

A.4. This expectation is sufficiently strong that I consider them to be my rights.

A.5. Virtue is the intuitive bedrock of our moral understanding of the world.

A.6. Reciprocity is the bedrock of social life.

B. Argument from introspection.

B.1. Others are also rational people capable of introspection, like myself.

B.2. They therefore possess similar needs.

B.3. Like myself, they expect to be treated accordingly.

B.4. Their expectation is sufficiently strong that they consider them to be their rights.

B.5. I ought to respect the rights of rational introspective people because I recognise them in myself.

C. Argument from virtue.

C.1. I am a virtuous animal(in my own eyes at least) who recognises, by virtue of our essential sameness, that the needs of others deserve respect.

C.2. Expecting my social needs to be granted while denying the needs of others would be an act of selfishness and a denial of my own virtuous nature.

C.3. If I am selective in practising virtue I cease to be a virtuous person.

C.4. Therefore I must extend my virtuous behaviour to all people.

Argument from reciprocity.

D.1. I am a social animal who derives great benefit from other social animals.

D.2. If I extract value from social organisation without due reciprocity I become a free-rider.

D.3. Free-riders damage the social order.

D.4. Selective reciprocity damages the social order both materially and morally.

D.5. Therefore I must practice reciprocity with all people.

In practice we limit our circles of concern to all similar people. We introduce distinctions based on familial, ethnic, cultural or regional differences. Stoic cosmopolitanism argues that essential sameness is more important than similarity, that we should make no distimctions.

But should we? Counter arguments could be practical ones such as:

– I have limited emotional energy. I must conserve this for those closest to me.

– Dissipating my concerns widely diminishes their effectiveness.

– I have better knowledge of the needs closest to me so will always attend to those more effectively.

– I am more strongly sensitised to the needs of those closest to me and this will more strongly motivate action.

– The immensity of global needs overwhelm me and this leads to inaction since my contribution makes so little difference.

– My local contributions have a visible impact and this motivates my continuing action.

– Seeing the beneficial effect of my contributions reinforces my virtuous nature.

My overall conclusion is this – feel global concern but express those concerns primarily in local action. But avoid or combat actions that heighten differences. Subject to the qualifications above, where ever possible make decisions based on essential sameness and not on local similarities.

LikeLike